In this fourth and final post about Playtests 1 and 2, we will discuss some of the parts of the game that were less visible, but if and when they changed would have altered the conditions noticeably for all players: the financial system. Linked to this is the bank, created prior to Playtest 2, and the market, which represents most of the outside world and what is going on there. These parts of the game that takes on the macro scale – and here it is good to remember that it is set in a small part of a small country – and so largely fall to Control to handle. This means that there must be a system in place for players’ actions to influence the macro scale, lest we end up with a roleplaying game in which the game master has decided which boss monster the players will face during the epic final battle. This is a megagame, and so there is no such thing as a set ending or a predictable way the players will navigate the obstacles an uncertain future throws at them – however, we will use scenario-like system which allows us to make quick decisions regarding which financial levers to pull and extreme weather knobs to turn depending on which way the players are leaning, leaving players to react to these situations and handle them in any way they can and find reasonable.

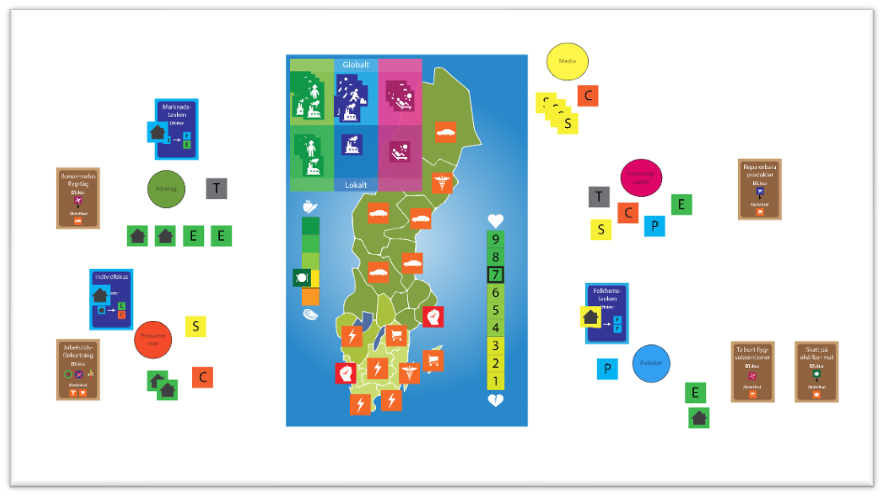

The least intrusive control mechanism is the market, which basically represents the rest of the world, from other parts of Sweden to the EU and beyond. Raw material shortages, price changes (up or down) for any resource, or even simply a headline on the news saying ‘unstable market’ are very subtle tools to change players’ outlook on almost anything on their game boards. Such events may also shift their attention from project cards promising a 30% reduction in electricity consumption as there is no raw materials to construct the passive houses, or it may be that something else they need all of a sudden becomes so costly that they simply have to postpone their construction plans to save some other part of their board from falling apart. However, players are in no way forced by Control to do something, roll any dice or take decisions other than if they can afford the resources they purchase from the market at the current price – the worst that can happen is that they no longer have access to a resource they depend on, in which case they need to get creative to avoid cascade effects.

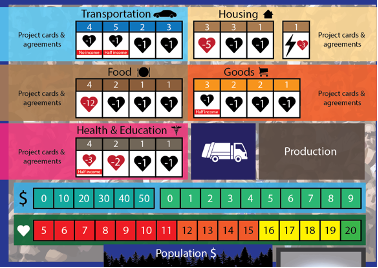

We have used this kind of effects to a limited extent and mostly in the form of price changes based on the gut feeling of members of the Control team. However, in future games we will structure this a little more: should a trade war have ensued during Playtests 1 and 2, the fact is that no member of the Control team knew the amount of e.g. Goods on the market, which means that a shortage could not be effectively implemented – all that would have happened was that there was no more Goods to be purchased, but all the Goods on the population and local authorities boards would have stayed where they are, making no impact on the game unless someone wanted to buy more Goods than they currently had. A more reasonable course of events would have been to announce a 50% reduction in Goods tokens across the board and a 100% rise in prices at the start of the turn, having players return their markers to the market and trying to negotiate black market terms with Control to be able to cover some of the losses of QoL and money.

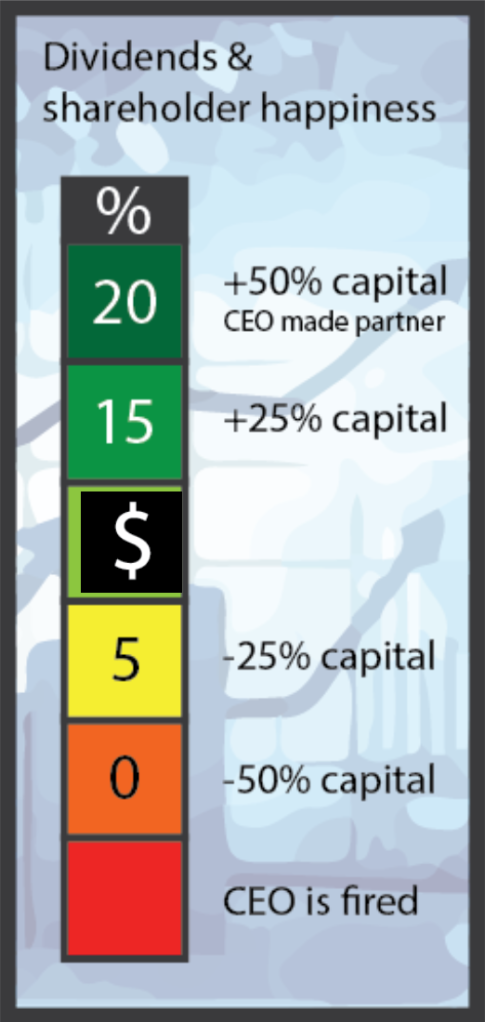

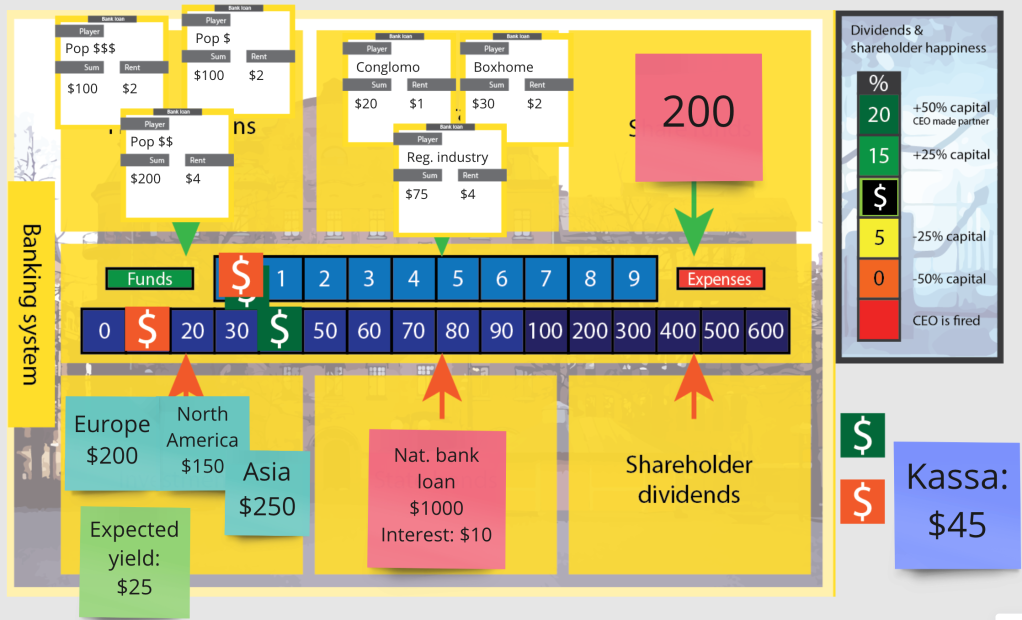

I found that the version used during Playtest 1 was unable to implement a worldwide depression in any other way than simply stating that it had happened. Thus, for Playtest 2 I created the bank board, which is meant to capture the essence of the clay feet of the financial system: the bank borrows money from the national bank, which it uses to give out house loans to the population and invest in shares in both domestic and foreign companies. I haven’t had the chance to run this part of the system by anyone with relevant expertise, but I’m hoping to do so before the next version sees light of day – what it is meant to do, however, is to provide Control with the ability to reflect the state of the world in ways that will create cascading effects in the game: the interest on the loan from the national bank goes from 1 to 5% overnight, which means the interest on house loans effectively puts the poorest population players out of a home, putting pressure on employers to raise wages, forcing them to increase prices, and so on. Also, plunging one continent into financial chaos means the bank needs to cover losses equal to the housing loans of a whole section of the population, which means they need to either increase the interest or increase their loan from the national bank. There are several ways this system can go wrong and create situations that make players look up and notice the world around them, very much like what has happened over the last few years.

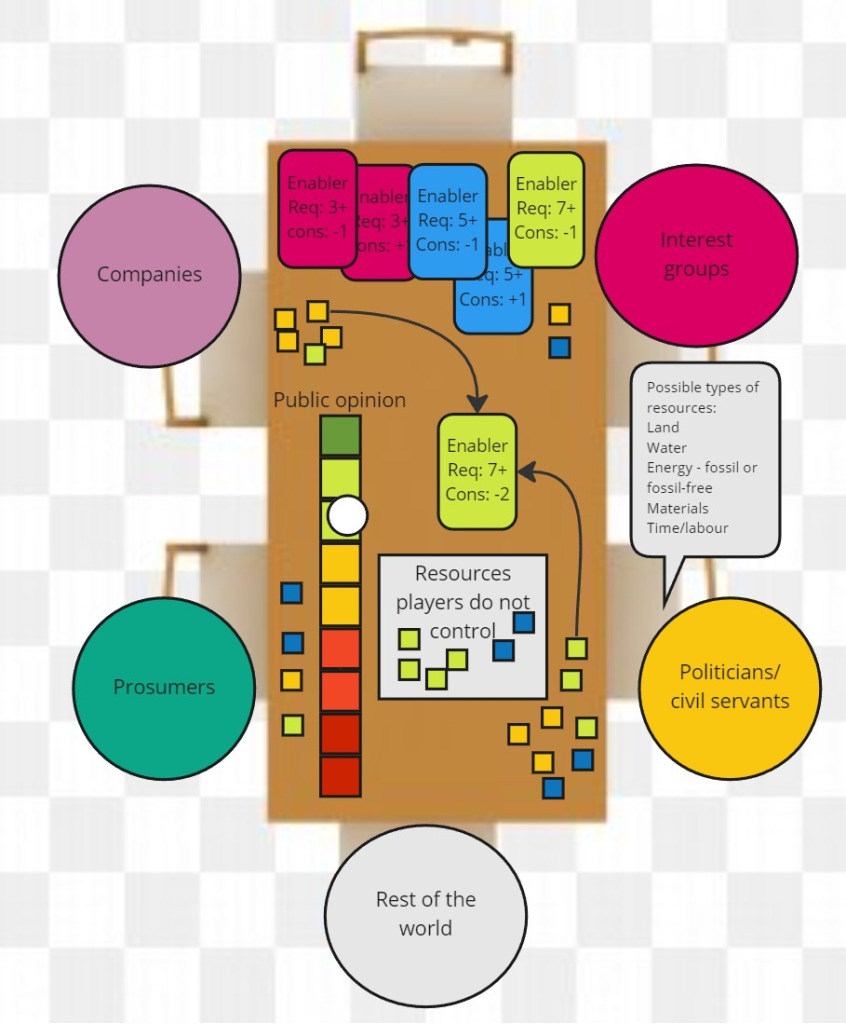

The purpose of the financial system is simply to provide Control with means of changing the conditions in the game – but where does the game end? Well, it could be anywhere, but as we’re working with the Swedish Energy Agency, we’re planning on using their Four Futures to create a scoring system that each turn will help Control decide on a set of external factors will be implemented, e.g. extreme weather events, local/global political incidents, etc. The scores will at first be based on which project cards the players implement – and should no cards be implemented, as was the case during Turn 1 of Playtest 2, there is a default scenario track which will send the players down the road of one of the four futures.

This is our way of using the setting to make sure that the Control team isn’t overwhelmed by all the questions from inexperienced players (which will make up almost the entire player base for this game), thereby preventing them from implementing more extensive changes to the exterior world. This has happened a couple of times during playtests, and this disappoints players as they feel that there aren’t any challenges aside from negotiating good deals with the other players, which is a full-time job in itself, but not the reason they came to play the game – after all, why play a game about making society more sustainable if the game setting does not in any way indicate that these changes are needed? These questions are related to the main learning goals of the game, and so the limited-number-of-scenarios system will be designed to enable players to reflect on the choices they made during the game and promote rewarding discussions during the debriefing after the game.

These are some of the thoughts that come up after the two first playtests – if you have ideas, questions, or want to contribute something from a player’s perspective, feel free to do so in the comments section: all ideas are welcome!