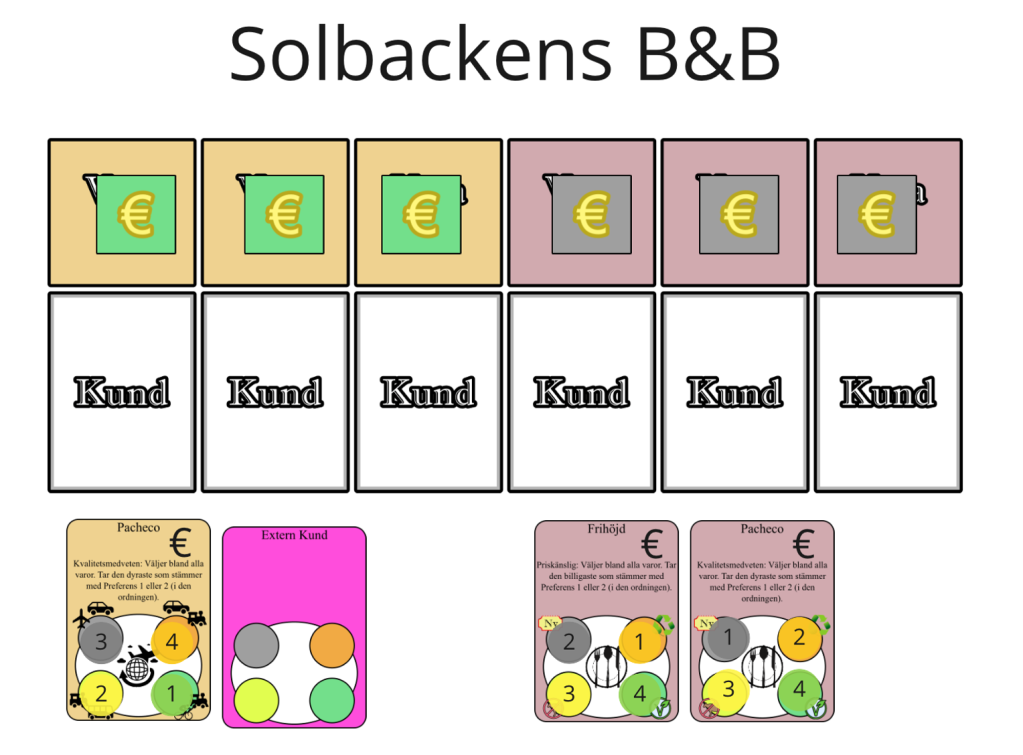

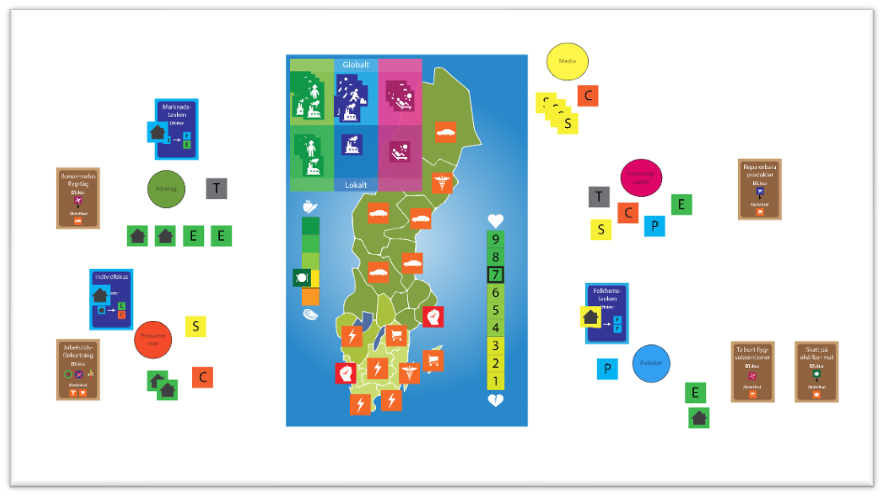

What became apparent in Wageningen was that we were onto something with this design, which centred on poker chips in different colours representing food, furnishings, and vacation and population teams assessing the well-being of their part of the population by comparing the piles of chips they had managed to get hold of during the round both to how they did last turn and also to the piles of the other teams. The conference participants were enthusiastically participating in what I later came to describe as an “intricate dance” in which population teams sold their workforce to companies and regional authorities (who turned it into products and service – and ultimately profit), and bought products from the same companies on the local market and received service in the form of police, healthcare, and education cards from the regional authorities teams. The economy was very much like a fishtank, meaning that financial decisions made by the players affected the whole system – and the interface with the outside world was almost exclusively the map and the world market, which very few players were interacting with, but through which the system in the fishtank was very much affected.

This first version underwent an overhaul a few weeks before we were scheduled to run a playtest in Västerås. The reason for this late change was that I realised something very important about the structure of the game: I had structured it for two-player teams that together would go through the entire sequence of actions in a single round, e.g. population teams would find employment (sell workforce chips) during Phase I, then go do some politics in Phase II, and lastly buy product chips in Phase III. The advantage with this structure was that teams stayed together, discussing every decision, and that teams could vary in size (even down to a single player) without any serious consequences.

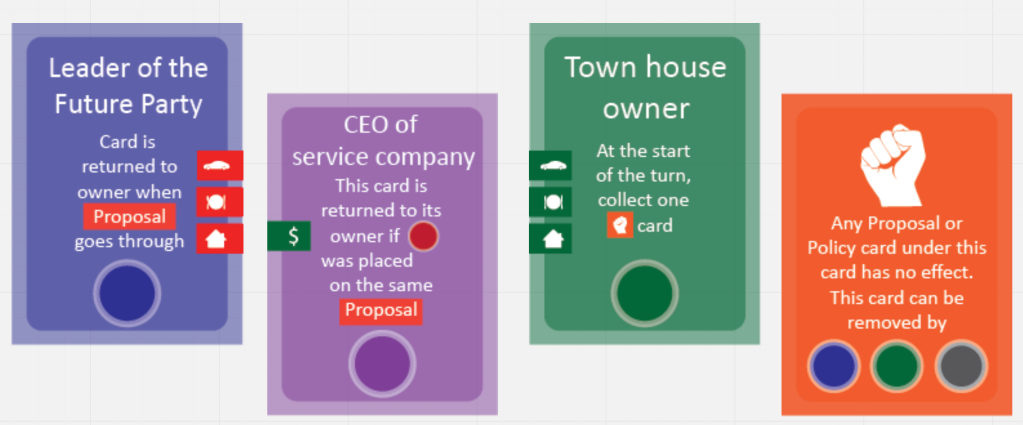

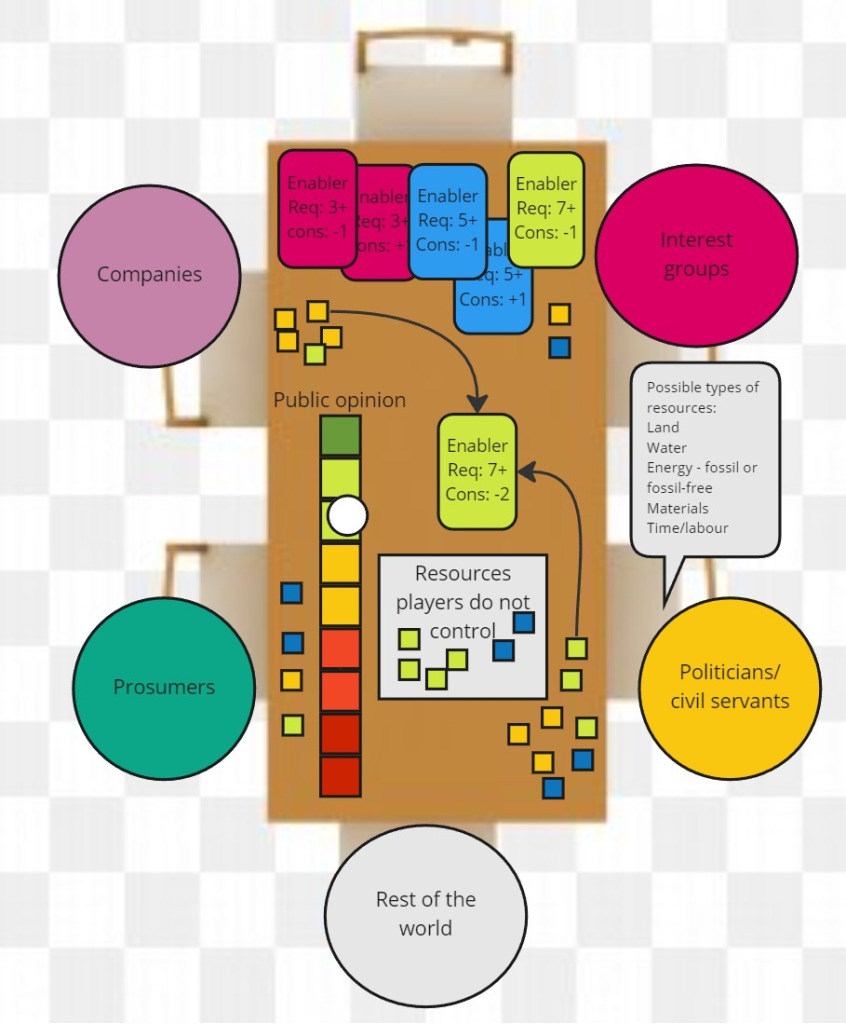

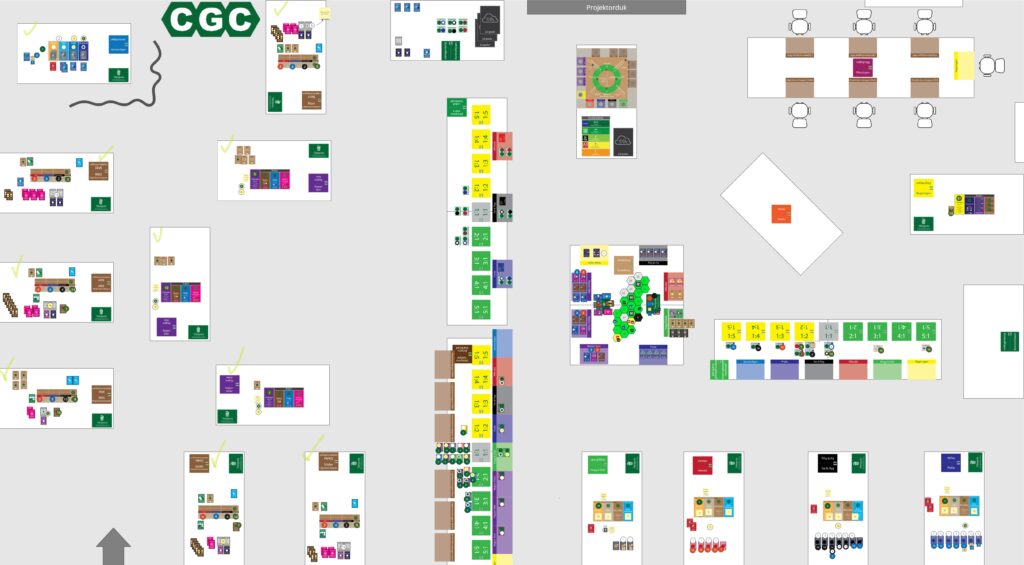

After running a Watch the Skies game in January 2024 I realised that the way the game was structured didn’t take advantage of the megagame structure in which several different subgames are played at once, with teams sending players to all or some of them simultaneously. I set out restructuring the game so that teams would consist of three players, each of which would go to one of five subgames: the labour market, the local market, the national assembly, the international market, and the production table/map. Population team players would go the first three, company team players to the local market and the last two, and regional authorities team players only to the last two. The implications for the game involved the effects of actions being delayed (increasing the price of imported goods on the international market on Turn 1 would cause prices to increase on the local market on Turn 2) and also that players would have to use their team time to discuss strategy, but would have to act on behalf of their team during the subgame, having to explain their actions and decisions to the rest of the team afterwards. My thinking was that this would make for a more interesting game experience and also involve some dynamics that exists in real life – and discussing my idea with people confirmed that they too saw this potential.

Above is a rough schematic of the flow of workforce (blue), food/goods/vacation/raw materials (black), public services (purple) and money (green) in the game. It was after I made this that I realised that what had been created here was an ‘intricate dance’, seeing as workforce, goods, and money needed to flow smoothly in order for the whole thing not to come crashing down. It did not do so during the three turns of the Västerås playtest, even though we had a shortage of players (two regions and one company were not played), and it remains to be seen if it will do so when played again with a full set of players.

I learned from this playtest was that the game is currently difficult to grasp as a first-time player, which may have caused things to go better in the game than they should have: it may be that players simply did not understand what they were supposed to do and so reused tokens that were supposed to have been thrown away. The two-page player briefings gave a step-by-step description of the game round, but that did not seem to have been picked up by the players, many of whom mentioned afterwards that they would have required step-by-step instructions, preferably in the form of an online instruction video, to understand what they were supposed to do. As we were playing with upper secondary pupils with no particular gaming experience (real-life or digital), this setup needs to be tested with older players to confirm if the game is currently too complex to be playable.

What I realised from this playtest was that what I had done was create subgames that acted as interfaces in different ways: the local and labour markets and the national assembly were formalised arenas for negotiation between players, the production table (and the resource aspects of the map) a ‘game mechanics handling area’, which is to say an interface with game mechanics, and the international market (and the strategic aspects of the map) map an interface with the scenario. The players could have handled all negotiations either at a flag saying “market” and mechanics by going to control and exchanging workforce and resources for chips, but formalising them made for simpler, more easily described actions for the players to perform, possibly representative of the structures in place in society that keep it relatively stable and predictable despite the myriad interactions between individuals taking place every second.

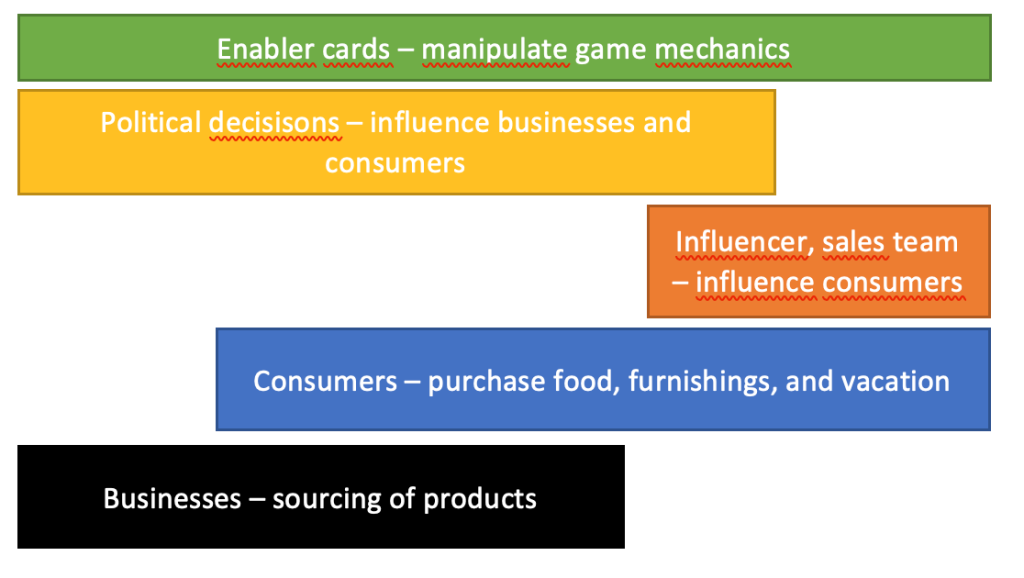

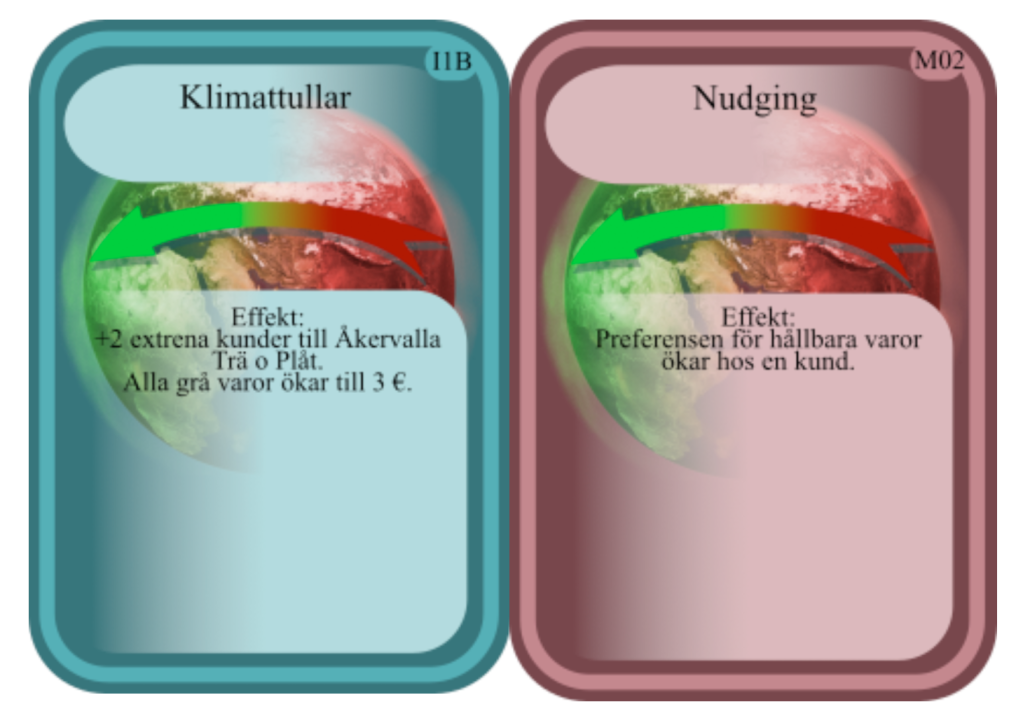

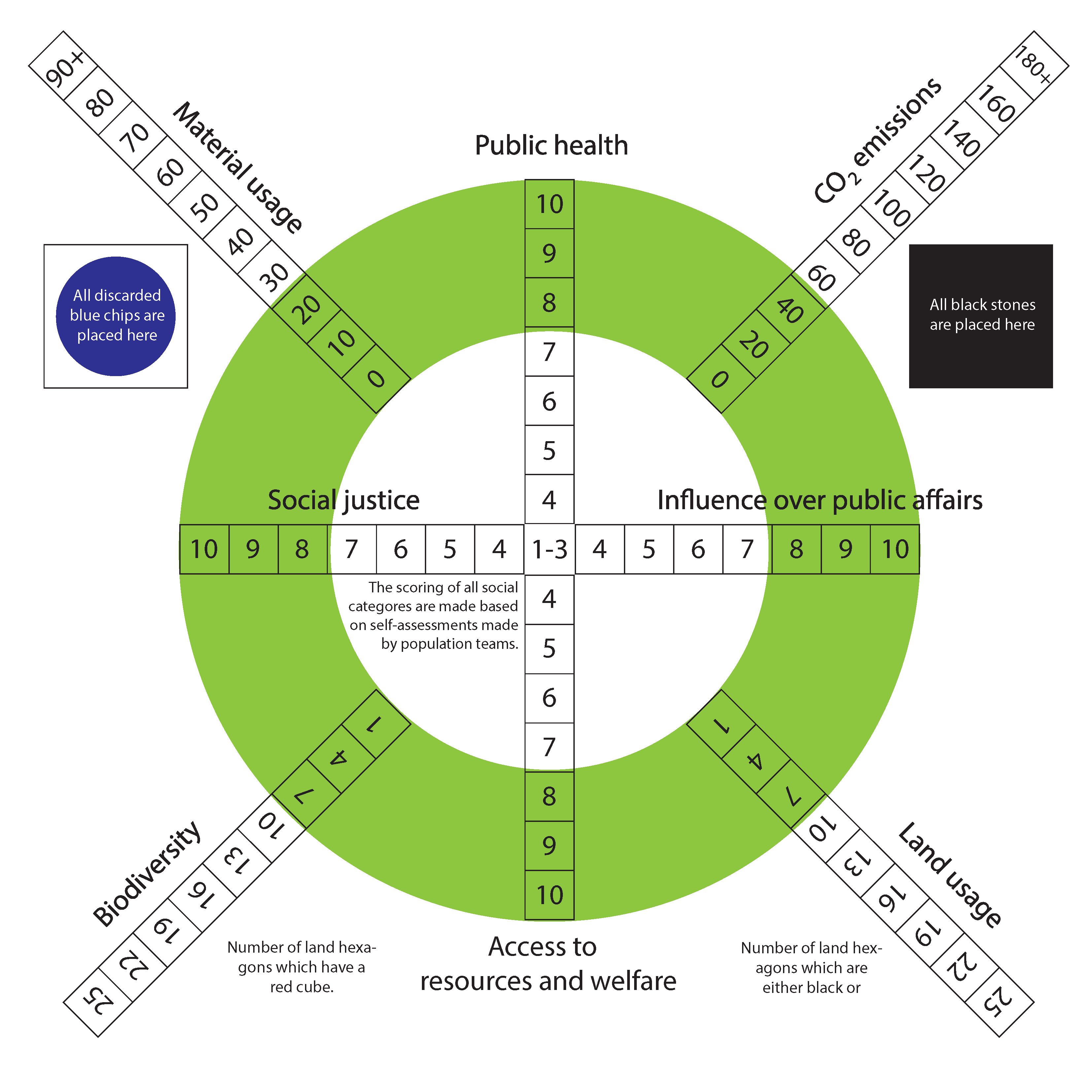

Based on this understanding of the structure of the game, I have come to consider a different take to the whole idea behind the game, which is to communicate the research results of the MISTRA Sustainable Consumption project. The current game illustrates (and quite elegantly so, if I may say so myself) the complexities of society and the structures that people have put in place to support it: the marketplaces, the assemblies, and the places of production, all of which are represented in terms of subgames. If we wanted to communicate just that, this setup would have been ideal – however, as we set out to communicate around the three focus areas of the project, i.e. how to sustainably consume food, furnishings, and vacation, I’m currently considering if there should be subgames for those three areas, along with perhaps production and political subgames, which focused on the effects of the list of enablers for sustainable consumption that has been proposed by the MISTRA project in much simpler terms. I will pursue this idea in the months to come, alongside developing and testing the version played in Västerås, which shows quite a lot of promise as a game.