The past week I’ve done a lot of designing (and redesigning) of game pieces. In this post, I’ll discuss how the design of game pieces in a megagame may impact players’ movement in the game room (and possibly destroy the game experience).

One of the major concerns of a megagame designer, Wallman argues, is keeping the complexity of the game mechanics low enough to allow a large number of players to play it without slowing the game down. In essence, this means I need to concentrate on the essentials, i.e. “what players must do first and foremost”, which also means reducing the minimum amount of movement and negotiation players as much as possible. The latter may be difficult for board game designers (such as myself), who are used games in which all players sit down around a table, having good overview and game pieces within easy reach. In a megagame, a player who wishes to do a simple sell/purchase action that would take seconds in a board game needs to pick up the game piece, walk over to another table (possibly being intercepted by someone who wants to talk or seeing something interesting they need to check up on), and there hopefully find the right person to talk to – even before negotiations on taking the buy/sell action begins. This takes considerably more time and also consumes a fair amount of focus, which is something a megagame designer needs to take into account.

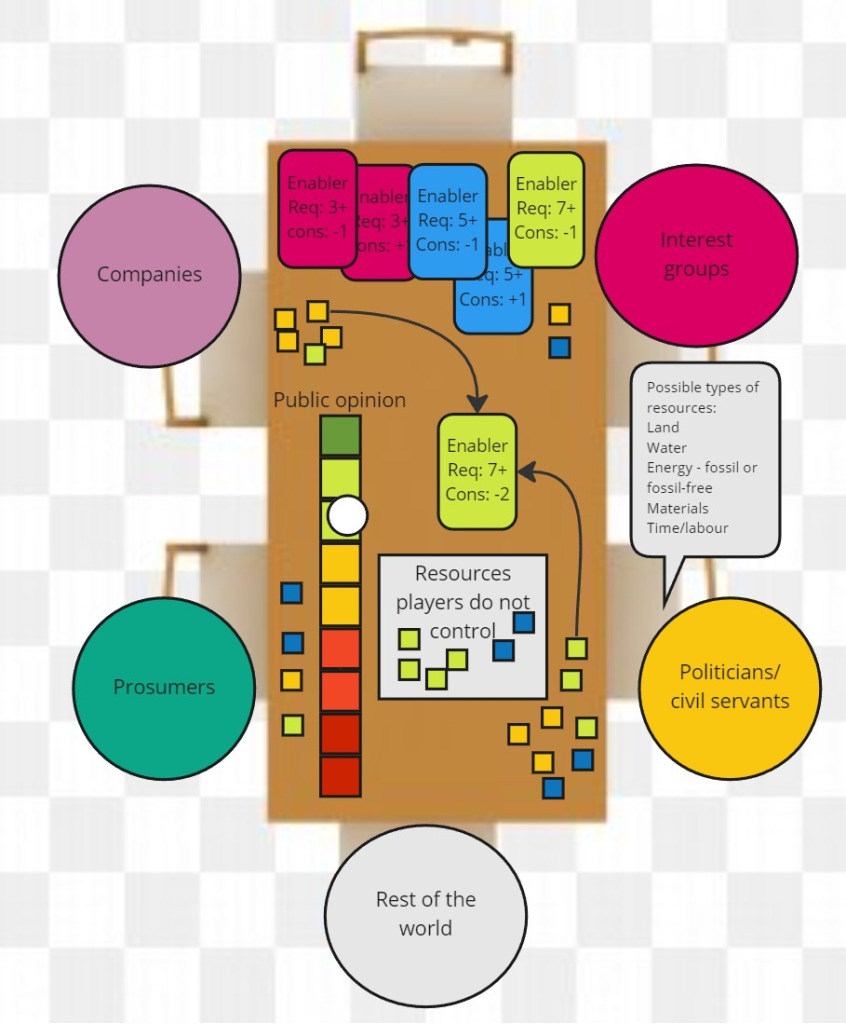

Our game focuses on energy various forms, and so various types of resources and their exchange for one another and money is at the centre of players’ attention. When designing the Climate Change Megagame we went up against a similar challenge, and having watched twenty people stand in line to talk to a very stressed salesman we reached the conclusion that we needed to use a ‘steady-state system’ in order to minimise the need for players to negotiate for the same resources every turn.

Thus, if a deal to purchase a resource that is consumed every turn (e.g. fuel or electricity) has been made, it will remain in place until one party wishes to break it (to sell the resource to someone else, or perhaps because the resource is no longer available due to e.g. market fluctuations or natural disasters), or change the terms on which it was originally struck (increase/decrease the price, exchange it for some other resource). This has implications for the beginning of the game too, as unless players do something other than go around to see which deals they already have in place, the affairs in the game will remain the same at the start of turn two as after setup. This means that beginners to the game (or even the megagame genre), who may feel a bit confused about all the new impressions and rules, may well spend their first turn looking around and talking to people without too much of a risk. This could be seen as a fair representation of the attitude of the vast majority of people to the climate question at the moment – it’s ‘business as usual’ until they can wrap their heads around what it’s really about and what to do about it.

The primary concern with a steady-state system in terms of game pieces is ownership of game pieces – in a computer game, the computer hands me a list of my game pieces, their location and what deals they are part of, but not so in a physical megagame. In addition to stressing the need to decrease the number of different resources each player handles as much as possible, this has two implications for the game: marking all game pieces so that it’s clear who owns each one of them and imposing a strict rule regarding how deals are broken or renegotiated.

The first is a matter of designing game pieces so that instead of having a bunch of generic ‘electricity’ tiles, each must have a coloured border that corresponds to the team/player to whom the tile belongs. This does not just mean more problems with sorting and storing game pieces, but also that it’s less easy to get change for a large-denomination resource as you can’t simply grab some from a nearby player but need to go to the player’s own stash. The biggest problem here is money, and in order to get away with making it generic, it needs to be placed in a specific way to show the terms of the deal.

Currently, Populations have Needs tiles that show a symbol for its category (Food, Goods, Housing, Transportation, Heath & Education) and a coloured square indicating which kind of energy (fossil, electricity, biobased) is required to fulfil it. For example, the blue team has an electric Housing Needs tile (blue border with a house symbol on a yellow background) that, at the start of the game, is placed on a 10-value Power Grid card (orange border with the number 10 and a power pole symbol on a yellow background) on the Electricity distributor’s (orange player) game board. Underneath the Housing tile is a coin (green circle with the number 5 on it) which is the price the blue Population player pays each turn for the power they use. As long as this stays this way, things are fine – the orange player has 5 money to spend each turn (some of which will be tied up in a similar way to secure the electricity needed to power the grid from the purple Electricity Producer), and the blue player has all the power they need to make people in their neighbourhood stay contented.

The moment someone wants to change this, however, they need to observe a simple yet crucial rule: a deal cannot be broken until the counterpart has been notified. This means that should the orange player want to get rid of the blue player’s tile, they can’t just simply take it and place it beside the game board, as that would mean the blue player – who thinks the deal is still on – will likely never know this has happened, and so go on playing as if they have all the power they need. Thus, the orange player must take the money and the blue tile and walk over to the blue Population player’s table and notify them of the fact that the deal is off. Similarly, if the blue player decide they can get a better price elsewhere – or they change to from electricity to heating with oil – they need to notify the orange player that they are taking their money and blue tile elsewhere.

Also, in this system money show up twice – as the money paid by the blue player for the power needs to stay put under the blue tile in our example, the orange player cannot just take it and spend it elsewhere, but needs to take a new coin and use that instead. When breaking a deal or negotiating a lower price for something, this would mean that the orange player needs to take the same amount of money from somewhere, which may not be done very quickly – they likely need to think about the implications and may need to renegotiate one or more deals – and so may cause not only serious chaos, but may require players and control to count the money spent and received for all deals the team/player is involved in throughout all the boards in the entire room, which may be detrimental to the game experience (and even more so should discrepancies be detected).

One solution to this problem is working with a money track, that may go below zero (short-term debt, in effect). This track is adjusted every time a player on the team makes a deal, and money tokens are simply used to show the value of deals. Thus, a player going over to another table to buy something worth 5 money would move the money track back 5 steps, take a 5-value money token from a central stash (overseen by control), and make the deal, whereupon the seller would move their money track forward 5 steps and start thinking about what to do with the money. When the buyer takes back their money, the seller moves their money track back 5 steps and start panicking about which deals they need to renegotiate so as not to end up on a deficit at the end of the turn, when interest on the credit they’ve run up is due.

There are a lot of ifs in this system, and should this system be too difficult for players to grasp and adhere to during a hectic game, parts of the purpose of the game may break down. Thus, the playtest on October 20 is set up to test if it works and if so, how they will improve on it to make things faster and smoother: players can almost always be relied upon to find shortcuts that a game designer would not come up with.

In my next post I’ll discuss my preparations for the playtest in terms of writing a rules document, which always results in interesting findings regarding things that need to be finetuned to make the game work better and which parts of it need a complete overhaul.