Since I last wrote I’ve been busy trying to structure the game design process for Playtest 3, which is scheduled to take place on February 6, 2023. This has meant going over which parts to make changes to and which to leave as they are – and this made me realise I haven’t had time to validate the economic system with someone who knows what they’re talking about. Luckily, I had been one of project members gave me a contact with an economic scientists, and what follows is what came out of our discussion of the game.

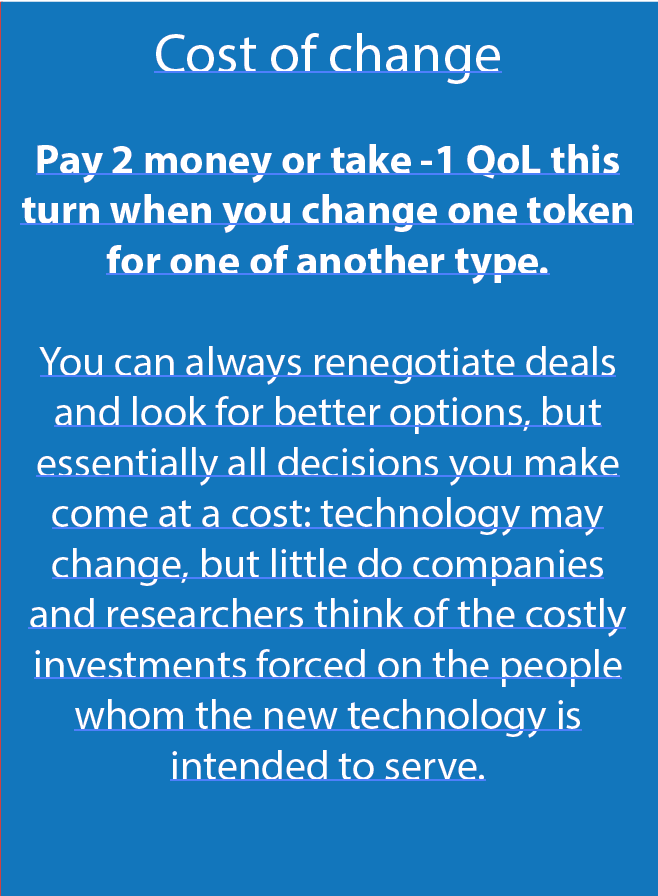

An important part of this game is that change is never free – there’s always a cost involved, be it in terms of money, time, or mental effort. This has been clear to me from the start, but the way this should be represented in the game has not, and so some input from the economic scientist was very welcome. He mentioned that research indicate that people need to feel that making a change provide them with a significant benefit – be it in terms of money or other values – for them to actually go through with a change such as the ones we are discussion in our game, e.g. changing from a fossil-driven car to an electric one. Being human myself, I knew this, but as a game designer I feared that the ease of exchanging one token for another on the gameboard would not be a high enough obstacle to make the choices players make in the game seem as realistic or difficult enough, so I’ve put in cards saying they have to pay money when changing from one type of token to another.

What I learned from Playtest 2, however, was that my fears were based on my being a board game designer – I had not considered the threshold of navigating a room full of people, talking to half a dozen of them, and then trying to make contact with the right person to get an idea if it would be possible to make the change, and what it would involve. I was somewhat misled by Playtest 1, which was small enough (12 people) that players could overview the situation to some extent, allowing them to take decisions that was more or less like those taken by a board gamer. So, when reminded of the fact that a deal must be significantly better – not just equally good or slightly better – I decided to exclude the mechanical cost of change and trust in the social one for the next playtest: after all, in Playtest 2 not a single change was made on the first turn and only one on the second, and that was only 19 players and they had not even looked their cards, due to miscommunication on the part of Control.

Another thing the economic scientist made me aware of is the scope of the retirement fund system, which made me realise that I need to include people’s saving money for (consumption in) the future in some way. The reason I want to look into this isn’t that I want the players to get a pension in the game, but that it may be used by Control to wreak havoc on the financial system – and the same is true for all the other parts of the game that involves the world at large. I’ll be considering putting in a team playing the Swedish income pension fund system, so as to put an emphasis on long-term investments in the financial system.

What I was most worried about was the shareholder happiness system, but as it turns out needn’t have been – instead I learned a lot about how I can integrate the share capital system even more into the game. The first part was that shareholders have a tendency to go where the money is, so when one company have a bad year, their capital moves to another company – or to state bonds or overseas investments, should such be on offer and promising a higher yield. This will make for an even more competitive atmosphere, which is further powered by the fact that the Swedish law states that CEOs aren’t allowed to compromise the profits of their shareholders, effectively tying their hands to make changes towards more sustainable solutions that involve great investments. That is, unless the shareholders – some of which are in the room, playing other roles – state that they are willing to accept lower dividends if the company also achieves goals tied to e.g. the sustainability of the energy system. The other option is to convince politicians to push for a change of the law, which might equally long – and may convince investors to place their money elsewhere if Swedish CEOs are free to ‘squander’ their money without discussing it with them first.

Whether players will work out this in time to actually make a change or simply try to work around it while the continual growth system simply goes on will be very interesting to see. What the potential development of this part of the game has made me realise, however, is that the stock market may need to be formalised into e.g. a separate board, so that players who own shares take time out of their turn to go there and take decisions about their money. This will prove to be a challenge, which may well be solved by developing the roles of the population players – their roles as a team become more complex, which gives room for more players and thus roles, one of which could certainly be handling the shares of the population, allowing them to focus on one aspect of the game rather than trying to see the whole picture the same way the role of is politician is already meant to. This opens up for further development of the array of roles given to population players – high-earning teams will have roles connected to politics and money, whereas other teams will have roles connected to practical and communication skills, making the teams differ from one another not only in terms of economic factors.

At the moment, the game is still in the process of expanding to handle all the aspects of the world that the project on achieving a sustainable energy system deems necessary. There will very soon come a time when reductions in terms of game pieces and mechanics and limitations in terms of how much of the world is represented in the game. As to this, I’ve received valuable advice from a megagame design colleague of mine, who pointed me to Ed Silverstone’s post on the Megagame Assembly blog and reminded me that megagame start in player interaction and add the minimum amount of mechanics to make it fly, whereas board games (which, as I mentioned earlier, is my backyard) use mechanics to achieve an experience. In this vein, one of my greatest challenges is that the connections between game boards and players must be very loose – so the fact that this game involves a tight-rope dance with balancing different energy types in a (in the case of electricity) more or less real-time system encompassing practically the entire room is less than optimal. There’s an energy system model in the background too, looking to be integrated into the game somehow – perhaps this is a good thing, as that will allow me to push interconnections between tables and players to the model, so that the game can work like a megagame rather than a huge version of Power Grid?