A week before the planned playtest of version 0.1 of the Changing the Game of Consumption megagame, two of our project members were to hold a one-hour presentation, and so came up with the idea of playing a short version of the game. This proved to be a welcome challenge, as it worked to question some of the ideas I put forward in my previous post and on which I had planned to base the first version of the game. Creating a 20-player version of a megagame with the time constraint of 60 minutes, including role distribution, rules explanation, and debriefing, would certainly prove Wallman’s point about the need to keep the complexity of the game mechanics low enough to allow a large number of players to play it without slowing the game down that is equally valid for the six-hour megagame we plan on creating. In this post, I’ll present the game I created and draw some conclusions regarding what parts of this can be used in the megagame.

My plan of using five different kinds of capital (economic, cultural, social, political, and technological) would be far too complex for this game, and so I boiled it down to that several players need to agree on a proposal for it to be implemented and that the time it took for players to negotiate would be the only resource they spent. However, as the game is so short (ten-minute turns) and some players may be more interested in winning than playing the game, they may skip negotiations and simply walk over to a table and state that they agree to all proposals, as they’re more concerned with the world not ending than about themselves getting the best deal possible as individuals. I’ve seen this kind of ‘altruism’ before, and feel that it cuts the game short in a way that doesn’t help players reflect on the world but rather leads them to comments about the game being unrealistic.

Thus, I decided that players would have to put their card down beside the enabler card and wouldn’t get it back until it was realised; this cost would stop blanket support and furthermore incentivise players to try to get others to sign on to help them get their cards back. Again, I saw before me a trio of smart players realising that they could simply realise all cards on a table with their three colours on in under a minute, then going on the next table, and then the next – after which they simply had to find a player with another colour on their role card and repeat the process, without need for negotiation, again breaking the game.

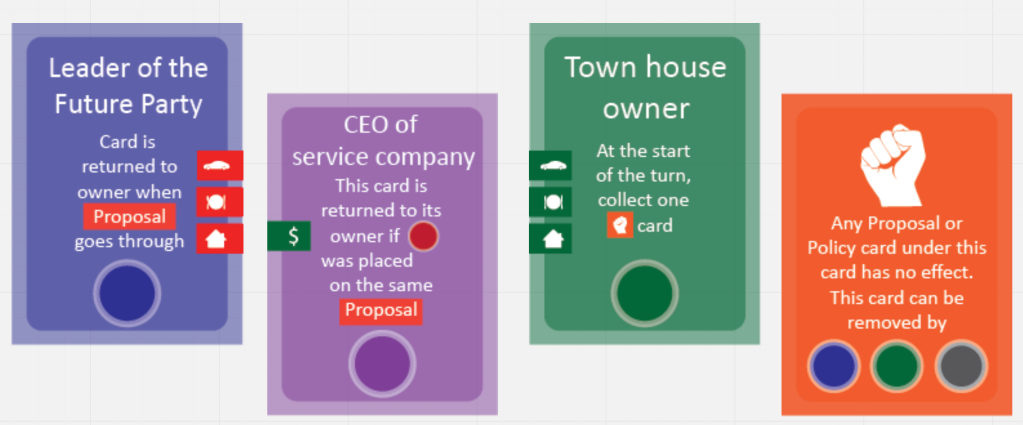

This dilemma paired with the realisation that the roles were rather vague – players wouldn’t have time to read role descriptions beforehand and come up with role interpretations – made me think of how to represent common interests in the form of game mechanics: I put tags on cards representing less/more (orange/green) of a number of basic ideas, such as individual means of transportation/vacation by plane (car symbol), meat-based diet (plate and cutlery), buying new furniture (house), and profit-driven market economy (dollar sign). This would guide players regarding which enabler cards were interesting for them (same symbol and colour as one of the tags on their role card) and which were directly opposing their goals (same symbol but opposite colour). After some thought, I added the rule that players would only get their cards back (and thus be able to use them again the same turn) after realising an enabler card with the same tag (symbol and colour) as one on their role cards.

These additions would both say something about the roles and prevent power gamers from ending the game on the first turn. There were another aspect that I felt I needed the game to communicate to, and that is that just because a bonus-malus system for flight travel has been agreed on, or an initiative to eat less meat or buy more second-hand furniture put in place, players would now be free to move on the next issue, as they had now ‘fixed’ the problem, as this is not how complex systems work (see Donella Meadows’s excellent book Thinking in Systems). Thus, I made all enabler cards two-sided with a cost to maintain it on the back – to ‘win’ the game, players would need not only to say yes to a bunch of exciting proposals, but also out in the work of maintaining them, every turn. This would also mean that players that didn’t like the proposal but were unable to stop them could negotiate with those who were to maintain the policy and offer them juicy deals on other proposals (more suited to their goals) to let the policy go back to being an unrealised policy again. This felt very much like how things work after the hype has passed, and so I felt it was worth adding.

After implementing the proposal/policy sides of enabler cards, I added some special abilities to role cards to make some players favour the hype around proposals and some disinclined to take part in it. One such pair is made up of politicians, who get their card back regardless of tags if they have supported a proposal, and government agencies, who get their cards back just for maintaining any policy. I also added other kinds of incentives, such as the ability of the Influencer role to once per turn return someone’s card to them (even themselves) regardless of tags, which could be used as a bargaining chip.

The original idea was to show projected CO2 emissions based on which enablers had been made policy and for how long they had been in place, but there was no time to implement this, so it may have to wait until the full version of the megagame. Instead, to give players a common goal and define an endpoint to the game, I set eight symbols (printed on the ‘policy’ side of most cards) in each of the three categories as a winning condition. As it turned out, three 10-minute turns were played and only a handful of enablers were flipped to their ‘policy’ side, so the goal was clearly too high in relation to the level of difficulty/complexity. It would perhaps have been more rewarding with some kind of projection to measure the impact the players in fact had on the world, and so this will be implemented.

As for other take-homes, I’ve realised that reducing the complexity of the game I envisioned earlier this autumn is a very good idea, as it will help players focus on the topic of the game and negotiations with other players. Also, some feedback from the participants in the game session suggested that the enabler cards were rather anonymous, i.e. as the title was the only text on the enabler cards they had very little idea what they were trying to accomplish, and so these need to be not only equipped with QR codes to allow players to read more about the findings of the MISTRA project, but also game mechanics such as tags and in-game effects that will help players decide which enablers they should spend resources and time getting off the ground (and maintaining).

Role descriptions are important parts of any megagame, and I’ll make sure to put in some work on those, both in terms of general descriptions and goals and game mechanics that help them play the game. I will also take some time to consider which roles are to be included, as the six groups used currently may not be the only ones. Also, the tags/categories of interests that I came up with didn’t exactly match the enabler cards, so that very few of them had relevant tags other than food/furniture/vacation, so work will have to go into finding connections between the cards that are more relevant.

This concludes this after-play reflections post, and in the next post I’ll discuss the workshop that was held in late November during which this version of the game was discussed.