In this post I’ll be going into some of the ideas that guide the game design process at this point. If some of them seem contradictory or very, very vague to you, that’s fine – the game is still in the concept stage, at which (at least to my mind) it’s quite alright to leave blanks to be filled in later. This work will eventually lead up to a prototype, which I’ll present to you in early 2023.

In the game, a number of players divided into teams will struggle to change the patterns of consumption of a population – for the moment we’ll assume that it’s the population of Sweden – to become more sustainable in terms of food, travel and furnishing. To their help they have various types of capital, e.g. economic, social, and cultural, that they can either use to gain advantages in the current system (following a ‘business as usual’ logic) or place on ‘enabler’ cards that may put the population on a slightly different path. The teams have different ideas of what ‘sustainability’ means and so do not necessarily agree on which enablers should be prioritised – or even realised at all. To top this off, events such as extreme weather and (inter)national crises and representatives of the powers of the outside world may influence their understanding of the enablers and what the future should look like.

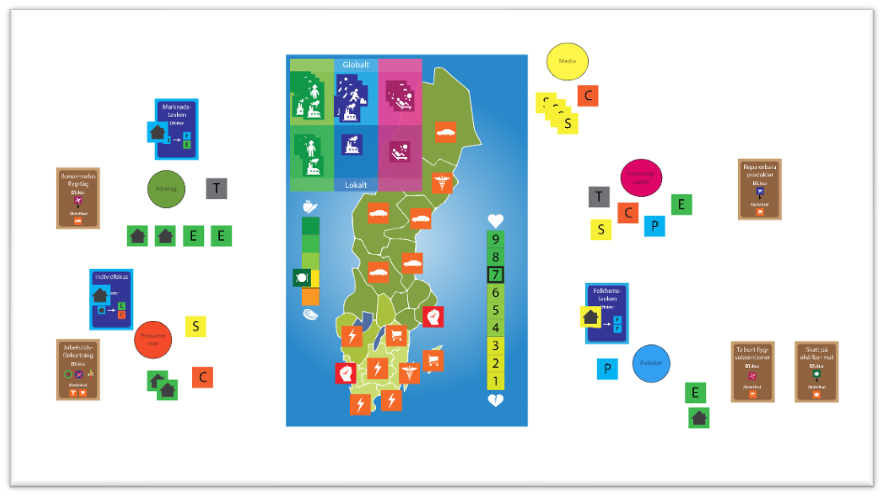

First of all, we need to describe the current situation, i.e. the consumption patterns of the population around which the game revolves. The current concept is based on the assumption that at the start of the game, the production of raw materials and products is more sustainable in Sweden than abroad. This may well be debatable as a general statement, but as we’re constructing a game, simplifications of this kind are necessary. Thus, we need to show where raw materials are sourced and production takes place, and below is my current attempt at showing this in the game:

Here, a distinction has been made between sourcing of raw materials and manufacturing of products – this may later be changed, but at the moment seems to reflect the fact that although factories are built in Sweden, the sourcing of raw materials needs to be done elsewhere for various reasons and so affects the overall environmental/CO2 impact of the products consumed by the population. The idea behind this section of the board is to make it easy to check progress and realise whether the game is going the way players want it to in terms of where production takes place and – although this may take closer inspection – either the current level of consumption and/or efficiency of operations (indicated by the number of tokens), and degree of sustainability. In the case of the food category, the track showing to the balance between meat and vegetables on people’s plates has been added to show degree of sustainability as it is pretty much universally agreed that meat leaves a much larger CO2 footprint than vegetables.

In my experience, most games benefit from including some kind of map, as it both gives players a sense of where the game takes place and allows for interesting conflicts based on geography, and so I decided to use a map of Sweden for the first version of the game. This immediately gave some ideas as to which issues are prioritised in different parts of the country, and so I put in some tokens to reflect the general idea that the sparsely populated north rely heavily on their cars to survive and the densely populated south rely on the north to provide them with energy, mainly electricity. Thus, any enablers that affect either availability of cars or electricity will meet with heavier resistance in some areas than others and e.g. a law banning fossil cars may cause riots (red tokens with a hand) in some areas unless players do something to ease tensions regarding this issue, e.g. pay out subsidies (economic capital) or appeal to the inhabitants emotions (social capital) or traditions (cultural capital).

Much of the game will revolve around negotiating with other players to put enabler cards into effect and so they will have to have a cost in capital that needs to be met. As players and teams will have different types of capital, they need to make deals with others to have them put in the right type of capital to activate the card. As we enter into a world that is already progressing (at full speed, some may argue), players won’t have a bunch of easily accessible capital to spend and instead will have most of it tied up in various projects and ideas. This is a way of representing society and bring to light the values that are embedded in people’s minds, such as a liberal market economy or – in the case of Sweden – Folkhemmet (the Swedish Welfare State). These may be very difficult to represent correctly, but play a very important role: they tie up capital in a way that provides players and teams with benefits (e.g. making one capital into two), which will have players think twice about e.g. shifting to a local economy based on small farming collectives in a single round – they may do so if they all set their minds to it (and many of the players will be against this), but the cost to all players will be very, very high as the population has a very different idea of what the future is going to look like and (unless faced with an extreme situation) will normally change their view on what’s a reasonable future very slowly, which in game terms involves spending large numbers of capital of various types over a number of turns. Here, ‘cost’ means decreasing the general state of mind of the entire population as represented by a track from 1–9 on the lower right on the game board – the lower it is, the more difficult will it be to implement enabler cards.

The concept I’ve outlined here is a long way away from playable a prototype, even if I’ve done some work on tokens and boards to help explaining my thoughts to myself and my team. As you may have noticed, I’ve not mentioned which players will be included and what their roles will be – the media was suggested as a group of players earlier this week, and I think it was a great idea so I added them above. In my next blog post, I’ll briefly discuss a slim version of this game that I constructed for a one-hour event that one of my project members held in mid-November, and which formed the basis for a workshop we held in late November.